From Avant Garde to Global Village

From Avant Garde to Global Village

Introduction

It could justifiably be stated that we are currently living in a Western World whose moral world view owes much to values which until recently were associated with progressives operating within the arts, politics, philosophy, religion etc., and that this morality remains more or less constant, affecting everything from top to bottom in our society, despite sporadic shifts of power from the political left to the right. At the same time, traditional morality - founded on the West's Judeo-Christian heritage - is being increasingly seen as harsh and exclusivist, where once it held almost total sway.

In order to come to some sort of conclusion as to how this situation came about, as good a starting point as any would be the early 19th Century, at a time when the Romantic Movement was birthing the concept of an artistic avant-garde on the cutting edge of innovation, not just in terms of creativity, but societal change.

Plausibly, the avant-garde worldview was the scion of a greater revolutionary spirit that had been impacting the West at least since the dawn of the Enlightenment, the great European move towards greater Rationalism regarding the key issues of life. The Age of Reason began towards the end of the 18th Century, lasting until about 1789, the year of the French Revolution, which was one if its earliest fruits.

Many theories exist as to what - or who - was the main driving force behind this spirit, but it's not the aim of this essay to attempt to unmask these, so much as to trace the course of the avant-garde throughout history, and so speculate on how so humble a tendency might ultimately have come to alter the entire fabric of Western civilisation through a process known as Modernism.

From Avant Garde to Global Village

It may have been the great English Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley who, by asserting that "Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world", was the first major artist to give expression to the concept of an avant-garde on the cutting edge of creative innovation. That said, the first actual use of the term in an artistic rather than military sense was probably made in 1825 by the early Socialist theorist Henri de Saint-Simon in his Literary, Philosophical and Industrial Opinions.

Whatever the truth, it's a recent development, fostered by the early, and especially German and English, Romantics, whose influence on the development of the notion of the Artist as Rebel cannot be underestimated. Yet, it arguably found its first spiritual home in post-revolutionary Paris. It's impossible to say precisely why, of course, but what is beyond dispute is that of all the nations of Europe, few could lay greater claim to national genius than France...and that this genius is most encapsulated in her ever-enchanting capital city. More particularly, though, by the 1830s, and following a long series of national traumas including the Revolutionary War itself, Paris had - I think it's fair to say - become the leading world incubator of the most charismatic originality of thought and behaviour.

It was a uniqueness, moreover, that has tended ever since to verge on the downright bizarre when manifested by certain of her most gifted citizens...such as her celebrated accursed poets - so-called, of course, for even the most malefic among us are capable of coming to faith in Christ - who have long been the ultimate apostles of the avant-garde.

It could be said that the first generation of these were numbered among the young men who - in the wake of the July Revolution of 1830 - congregated about such wild and brilliant youth as Petrus Borel and Theophile Gautier, two writers of the so-called frenetic school of late Romantics. They did so with the purpose of enforcing the Romantic worldview in the face of widespread censure on the part of the despised respectable middle classes.

To the Gautier of the mid 1830s, this censure constituted a veritable Christian moral resurgence, which he rails against in the famous preface to his 1836 novel, Mademoiselle de Maupin, the first known manifesto of the doctrine of Art for Art's Sake.

These seminal avant-gardists have become known as the Bouzingos, although little distinguished them from the earlier Jeunes-France.

They were originally members of the Petit Cenacle, a Romantic clique allegedly founded by the sculptor Jehan du Seigneur, whose role in the infamous Battle of Hernani at the Comedie-Francaise theatre in February 1830 was paramount. This took place on the opening night of Hugo's play, Hernani, and was marked by violent scenes involving defenders of the Classical tradition, and Hugo's supporters, who flaunted long hair and flamboyant costumes in defiance of everything the former held dear. In addition to Gautier, Borel and Seigneur, they included Gerard de Nerval, Philothee O'Neddy and Augustus MacKeat, all of whom went on to be numbered among the Jeunes-France.

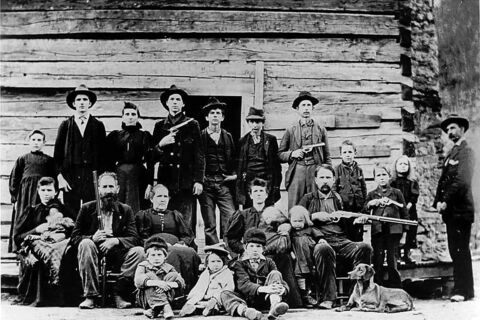

According to one theory, while the first Bouzingos were a band of political agitators who took part in the July Revolution in wide-brimmed leather hats, their artistic counterparts were wrongly named by the press following a night of riotous boozing which saw some of them end up in prison for the night. They too embraced radical political views, because for the most part, the artistic avant-garde has inclined to the left, while containing an ultra-conservative element.

Needless to say perhaps, they owed an enormous debt to the earlier English and German Romantics, who did much - or so it's been asserted - to promulgate the myth of the tormented artist ever-existent on the fringes of respectable society...which later came to be known as Bohemia.

Akin to the bohemian was the dandy; and of the purported accursed poets of mid 19th Century Paris, several were both bohemians and dandies, depending on their circumstances at the time. They included Charles Baudelaire, whose 1863 essay The Dandy is one of the defining works on the subject.

The great Parisian Bohemias of the 19th Century were the Left Bank of the Seine as a whole - including the Latin Quarter and Montparnasse - and Montmartre, which exploded on an international scale towards the century's end; while the first literary work to officially celebrate the Bohemian way was Henri Murger's Scenes of Bohemian Life.

Later Bohemias included London's Chelsea, and New York's Greenwich Village, but Paris remains Bohemia's true and eternal spiritual capital.

The first waves of the avant-garde, and the Bohemias in which they thrived, ultimately produced the Decadent movement of the 1870s and '80s, and a multitude of minor sects, such as the Zutistes of the early '70s, which for a time included Verlaine and Rimbaud, and the later Hirsutes and Hydropathes, and finally, the great Symbolist Movement in the arts.

However, the spirit of the avant-garde could be said to have triumphed as never before in the shape of the massively influential and truly international artistic and cultural phenomenon known as Modernism.

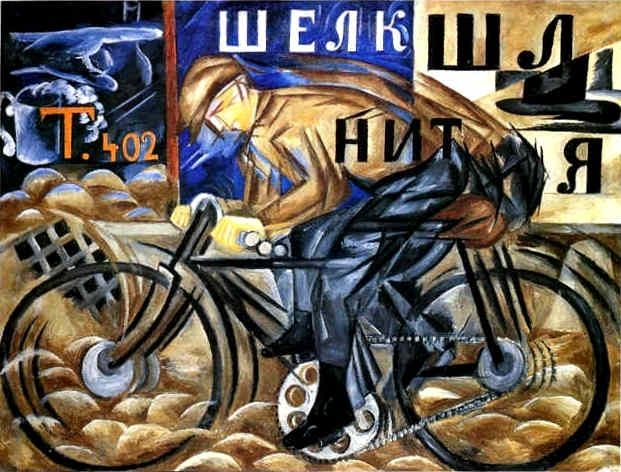

In an artistic sense, she existed at her point of maximum intensity from about 1890 to 1930, producing such earth-shaking works as Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring (1913), T.S. Eliot's The Waste Land (1922) and James Joyce's Ulysses (1922). Mention must also be made of such Modernist schools as the previously mentioned Symbolism, as well as Expressionism, Futurism, Dadaism and Surrealism. It could be said that she represented the triumph of the avant-garde, anticipating her future at the very heart of the cultural mainstream.

Furthermore, whenever Modernism is discussed with regard to the arts, parallel iconoclastic developments by figures such as Marx in politics, Nietzsche in philosophy, Freud in psychology, and Darwin in science must surely be taken into consideration. They all served to fuel the Modernist agenda, which - according to certain cultural critics - is intrinsically anti-Christian...and there is substance to their argument, although several major Modernist figures have been professing Christians.

Taking things further, it could be averred that rather than emerging from the avant-garde, Modernism actually predated it, that is, as a spirit rather than a movement as such, having roots further back into the depths of Western history, beyond the Age of Reason, to the Renaissance and its revival of Classical Antiquity.

She seemed to undergo a falling away in terms of intensity in the years leading up to the Second World War, while the immediate post-war age brought renewed activity through the Existentialists and Lettrists of Paris, but more especially through the Beat Generation, born in the city which had recently become the cultural capital of the world: New York.

Together, they helped to usher in what could be called an age of Mass-Modernism, although they weren't operating alone, because by the early '50s, the Modern had formed a strong alliance with the popular arts. In fact, this had occurred some half century earlier with the genesis of Pop Culture, which gave rise to the cinema, and one of the first true Pop music genres in the shape of Ragtime. However, these were minor developments in comparison to the cataclysmic events of the '60s.

Possibly the single most powerful weapon in the Modernist armoury has been Pop Culture, and in terms of its evolution, the influence of the Beat Generation was enormous. That is especially true of its role as the begetter of the Hippie uprising, which took place between about 1965, with San Francisco as its centrifugal city, and 1967 when it peaked, before ceding to the year of revolutions, which was 1968.

One of the keynotes of late Modernism and the social revolution it provoked, most notably in the 1960s, has been the progressive acceptance by mass culture of beliefs once seen as the preserve of bohemians and avant-gardists, the most obvious being the so-called "free love" once promoted so forcefully by angel-faced atheist, Percy Bysshe Shelley.

This process was considerably facilitated by the Rock revolution which, after having begun around 1955-'56, segued into the sentimental Pop music that reached its apogee with the Beatles. It then underwent a further quickening at the hands of harder, earthier bands such as those of the first British Blues boom; and so evolve into Rock pure and simple.

By the end of the '60s, Rock had become a truly versatile music, running the gamut from the most infantile hit parade ditties to musically and lyrically complex compositions owing as much to Classical music and Jazz as Rock and Roll. As such, it was an international language, with the power to disseminate values hostile to traditional Western morality as no other artistic movement before it, while the most powerful Rock stars attained - if only fleetingly - through popular consumer culture a degree of influence that previous generations of innovative artists operating within high culture could only dream of.

Yet, as the ultimate manifestation of what might be termed Mass Modernism, Rock has not functioned alone; in fact, from the outset, it was impelled by the cinema of youthful discontent of the early 1950s, whose magnetic icons, including Monty Clift, Marlon Brando and James Dean, could be said to have been Rock stars before their time. Furthermore, as the Rock revolution proceeded apace throughout the '70s, it was buttressed and enabled by a cinema finally freed from the shackles of the Motion Picture Production Code, which had been in force since 1930 but which was finally jettisoned in 1967, after at least a decade of declining efficacy.

At some point in its recent history, Modernism's unrelenting drive towards permanent societal change arguably reached a logical conclusion, as the classic values of the avant-garde had begun to wholly dominate the cultural mainstream; and so the West entered a Postmodern phase. When this occurred is open to conjecture, but 1980 has been put forward as a likely date. Certainly, after 1980, it became impossible for artists to scandalise the bourgeoisie as they'd once done; and even when they strained to shock a public all but impervious to outrage, originality eluded them. Others have insisted Postmodernism began as early as 1950, on the eve of the television and Pop Music revolutions.

What is certain is that things have changed beyond all measure in the West in the last half century or so to the extent that in the 2010s, the age-old dream of political and artistic radicals, and their allies within the realms of religion, philosophy, psychology, science etc., of a world united by humanitarian values could be closer to becoming a reality than has ever been possible up to this point in time. In the meantime, the old world, the Judeo-Christian one bound by love of God, love of country, and love of family, has to all intents and purposes been cast out into the wilderness, as if there can be no place for its ancient certainties in the paradise about to be born.