The Gambolling Baby Boomer

Chapter One The Gambolling Baby Boomer

Birth of a Rock and Roll Child

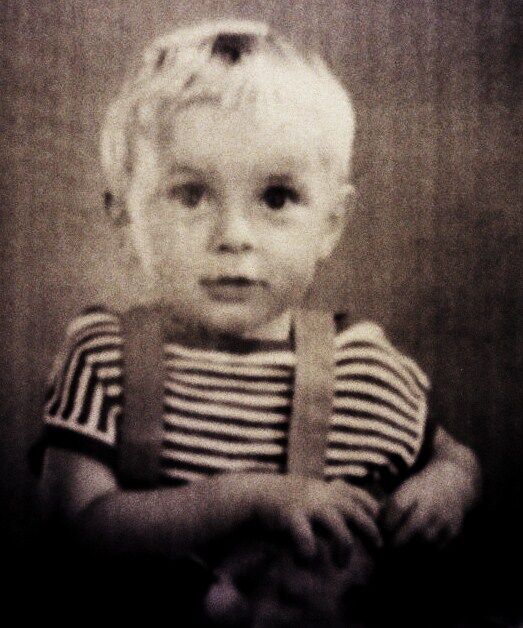

I was born a Londoner at the tail end of a street called Goldhawk Road to the west of the city, and my first home was a little Victorian cottage in the long-demolished Bulmer Place in Notting Hill. You'll search in vain for this poky little street in any London map, although you'll still be able to locate a Bulmer Mews tucked away some yards away from the main road of Notting Hill Gate.

On the day I was born, Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad, radical psychologist RD Laing, controversial war hero Colonel Oliver North, Laurel Canyon songstress Judee Sill, conservative activist Paul Weyrich, and Russian politician Vladimir Putin celebrated their 58th, 28th, 13th, 11th and 3rd birthdays respectively, while Beat poet Amiri Baraka, left-wing revolutionary Ulrike Meinhof, and Falklands War commander Major Julian Thompson all hit 21.

What's more, it was marked by an event which had a colossal if largely unrecognised influence on the evolution of our culture, one known as the Six Gallery reading, or Six Angels in the Same Performance.

On the evening of the 7th of October 1955, about 150 people gathered at San Francisco's Six Gallery to witness readings of poems by Allen Ginsberg, Phillip Whalen, Phillip Lamantia, Michael McClure and Gary Snyder, all of whom went on to be leading lights of the Beat Generation. As to the future King of the Beats, Jack Kerouac, he attended but didn't read, preferring to cheerlead instead in a state of ecstatic inebriation. His On the Road published two years later, and dealing with his wanderings across America with his muse and friend Neal Cassady, remains Beat's most famous ever work.

After the Six Gallery reading, the Beat movement, which had existed in embryonic form since about 1944, left the underground to gradually mutate into an international craze, so that by the end of the decade, the Beatnik had taken his place as a universally recognised icon with his beret, goatee beard, turtle-neck sweater, sandals and so on.

1955 was also the year in which Rock and Roll made its first major impact on the mainstream as a result of record successes by R&B artists such as Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry and Little Richard. However, it's The Blackboard Jungle, which, released on the 20th of March, is widely with igniting the Rock and Roll revolution, indeed late 20th Century teenage rebellion as a whole. It did so by featuring Bill Haley & His Comets' cover of Sonny Dae and His Knights' Rock Around the Clock over the film's opening credits. Haley's version, which was remarkable for its earth-shaking sense of urgency, ensured the world would never be the same after it. Then in August, Sun Records released a long playing record entitled Elvis Presley, Scotty and Bill, featuring a young truck driver from the small town of Tupelo, Mississippi. He went on to become Rock's single most influential figure apart from the Beatles.

On the 30th of September, James Dean died in hospital following a motor accident at the appallingly early age of 24 after having made only three films, the most symbolic of which, Nicholas Ray's Rebel Without a Cause emerged about a month afterwards. It could be said that Rebel is the motion picture industry's defining elegy to the rebelliousness of post-war youth, and that as the latter's ultimate icon, Dean's beautiful, tortured image has never dated, nor been surpassed. And that the modern cult of youth was born in the mid 1950s.

Many theories exist as to how the staid conformist fifties could have yielded as if by magic to the wild Dionysian sixties, some convincing, others less so. For me, if a little leaven is present in a theory for me it leavens, or spoils, the entire lump, even when much of it may be sound. Far from being a sudden, unexpected event, the post-war cultural revolution has historical roots reaching at least as far back as the so-called Enlightenment, since which time the West has been consistently assailed by tendencies hostile to its Judeo-Christian moral fabric.

What happened in the 1960s was as I see it simply the culmination of many decades of activity on the part of revolutionaries and avant-gardists, which had been especially intensive since the First World War. Even Rock, a music which the American evangelist John MacArthur once described as having a bombastic atonality and dissonance was foreshadowed at its most experimental by the so-called “emancipation of the dissonant” brought about by Classical composers of various Modernist schools.

Still, for all the change that raged around me as a child growing up in sixties London, my own little world was an idyllic one; and on the surface of things, I imagine the capital's western suburbs had altered little since the day I was born when the spirit of Victorian morality could be said to have been yet more or less intact in Britain. Although on a more radical level, I think it's fair to say she'd undergone what could be called a colossal transformation in the brief few years since the dawn of the previous decade.

My brother was born just a little over two and a half years after me, by which time my parents had been able to afford their own house in Bedford Park in what was then the London Borough of Acton. Built by Norman Richard Shaw, Bedford Park was the world's first Garden Suburb. By the 1880s, it was a Bohemian centre for intellectuals and artistic free-thinkers its residents going on to include most famously the great Anglo-Irish poet WB Yeats. The painter Arthur Pinero was another resident; as was the actress Florence Farr, who like Yeats was deeply involved in mysticism and the occult.

Some time after the dawn of the next century, the area had declined to the extent that bus conductors would allegedly shout out “Poverty Park!” when their vehicles came to a halt at the local stop. However, the foundation, in 1963, of the Bedford Park Society led to the listing of 356 houses by the government, and so, much of the estate becoming part of the Bedford Park Conservation Area. During my boyhood it was still demographically mixed, yet well on the way to becoming completely gentrified.

Future Who front man Roger Daltry had relocated there from inner West London when he was 11 years old in 1955 or '56. A few years later, he formed a group in the Skiffle - or Jug Band - style called The Detours. Once it had shape-shifted into The Who, its furiously hedonistic music and philosophy would go on to make a permanent impression on the Western psyche and help fuel the British Invasion of America.

Tales of Patrick Clancy and Miss Ann Watt

By the time we moved to Bedford Park, My father had been working steadily as a Classical violinist for some years, and so was in a position to ensure that my brother and I enjoy a far more stable childhood than his had ever been.

He'd been born Patrick Clancy Halling in Rowella, Tasmania, and raised in Sydney as the son of a Danish father, Carl Christian Halling, and an English mother, whom we always knew as Mary, although she'd come into the world as Phyllis Mary Pinnock possibly in the Dulwich area of South London sometime around the turn of the 20th Century.

According to the only known photograph of her in her youth, she grew into a lovely young woman, with straight dark hair, beautiful, possibly green, eyes, and a finely sculpted mouth; but with great beauty come great expectations, and also sometimes great sorrows too. They certainly did in the case of Phyllis, who lost the purported first love of her life in the First World War, who - evidently serving as an airman in what may have been the Royal Flying Corps - was shot down, possibly over France, and so died in action like so many others of his generation. Not so long afterwards, she wed an officer in the British Army by the name of Peter Robinson, and they had two children in quick succession, Peter Bevan, and Suzanne, known as Dinny.

According to Mary's sister Joan, their maternal grandmother's maiden name had been Butler, which allegedly links the family to the Butlers of Ormonde, a dynasty of Old English nobles of Norman origin which had dominated the south east of Ireland since the Middle Ages, and so making it a lost or discarded branch. If Joan was right then I'm related by blood to many of the most prominent royal and aristocratic figures in history, perhaps even all of them. These would include her namesake Lady Joan FitzGerald, daughter of James Butler the first Earl of Ormonde, and alleged ancestress of Diana, Princess of Wales. Lady Joan herself was the granddaughter of Edward the 1st of the House of Plantagenet, that Anglo-Norman king (dubbed “the Hammer of the Scots”) who'd had Scottish noble Sir William Wallace executed in 1305 for having led a resistance during the Wars of Scottish Independence. Her mother, Eleanor de Bohun, was descended from Charlemagne, the greatest of all the Carolingian Kings, the Merovingians and Carolingians being two dynasties of Frankish rulers who supposedly upheld the divine right of kings. He may also have been Merovingian through his great-grandmother, Bertrada of Prum.

At some point between Peter's birth and that of his younger brother Patrick, she travelled with her husband to Ceylon - now Sri Lanka - in order that they might both work as planters on the famous Ceylonese plantations. There she met the aforesaid Carl Halling. What followed next I can't say for sure but I've been led to believe that at some point after becoming pregnant with her third child, Phyllis went to live with Carl on the island of Tasmania. There my father was born in the beautiful Tamar Valley near the capital city of Launceston. By this time, his parents were working as apple farmers; or so I can recall his telling me.

However, Pat was raised not in Tasmania but the great city of Sydney, New South Wales, which is where poor Carl contracted Multiple Sclerosis. After this, Phyllis made a living variously as a journalist and teacher, or so I've been told, although I'm uncertain of the exact dates, writing for the Sydney Telegraph, and running her own elementary school. As to Carl, his desperate search for a cure for his MS allegedly included an involvement with the Christian Science movement, among other spiritual recourses according to Pat.

But sadly he died just before the outbreak of World War II, and according to his wishes, was buried in his native Denmark.

All three children had earlier displayed considerable musical talent, Patrick as violinist, Peter as cellist and Suzanne as pianist. Pat has told me that he was only around nine years old, and a student at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music, when he served on one occasion as soloist for the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, a pretty impressive feat for one so young.

Soon after Carl's burial, Mary set off for London alone, apparently in search of a suitable place of residence, while the children remained behind with family in Denmark, joining her at a later date.

Pat studied at both the Royal Academy of Music and the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, and joined the London Philharmonic Orchestra while still a teenager during the Blitz on London, serving in the Sea Cadets as a signaller, and seeing action as such on the hospital ships of the Thames River Emergency Service.

By this time, my mother, the former Miss Ann Watt, was already a highly accomplished and successful singer of both classical and light music, notably with Vancouver's legendary Theatre Under the Stars.

She'd been born Angela Jean Elisabeth Watt in Brandon, Manitoba. However, while still an infant she'd moved with her parents and four siblings to the Grandview area of East Vancouver. Grandview's earliest settlers were usually tradesmen or shopkeepers, in shipping or construction work, and largely of British origin. My own grandfather James Watt, who evidently worked at various times as a farm labourer, builder and electrician, had been born in the little town of Castlederg in County Tyrone, Ireland, then part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

Her mother, Elizabeth Hazeldine, was from the Springburn area of Glasgow, Scotland, having been born there according to my mother to an English father from either Liverpool or Manchester, and a Scottish mother. She was the youngest of six siblings, and while she was alone among her immediate family not to have been born in Britain, she was also the only one to seek permanent residency in the mother country.

Within a short time of arriving, she met my father through their shared profession, and they married in the summer of 1948. Seven years later, they decided to have their first child, and so I was born a Londoner, Carl Robert Halling at 3.50 in the afternoon of Friday the 7th of October.

(A Child's) Swinging Sixties London

I was an articulate and sociable kid from the word go, walking, talking early just like my dad before me, but agitated, unable to rest, what they might call hyperactive today.

My first school was a kind of nursery school held locally on a daily basis at the private residence of a lady named Miss Pearson, and then aged 4 years old, I joined the exclusive Lycee Francais du Kensington du Sud, situated in the fabulously opulent West London area of South Kensington, where I was to become bilingual by the age of four or thereabouts.

Almost every race and nationality under the sun was to be found in the Lycee in those days...and among those who went on to be good pals of mine were kids of English, French, Jewish, American, Yugoslavian and Middle Eastern origin.

My father was far from wealthy, but he was determined that my brother and I enjoy the best and richest education imaginable, and we were dressed in lederhosen with our heads shorn like convicts, so that we be distinguished from the common run of British boys with their short back and sides, and to this end, he worked, toiled incessantly to ensure that we did.

At some stage in the early 1960s, I became a problem both at school and home, a disruptive influence in the class, and a trouble-maker in the streets, an eccentric loon full of madcap fun and half-deranged imaginativeness whose unusual physical appearance was enhanced by a striking thinness and enormous long-lashed blue eyes. Less charmingly, I was also the kind of deliberately malicious little hooligan who'd remove a paper from a neighbour's letter-box, and then mutilate it before re-posting it.

The era's famous social and sexual revolution was well under way, and yet for all that, seminal Pop groups such as the Searchers and the Dave Clark Five - even the Beatles themselves - were quaint and wholesome figures in a still relatively innocent Britain. They fitted in well in a nation of Norman Wisdom pictures and the well-spoken presenters of the BBC Home or Light Service, of coppers, tanners and ten bob notes, sweet shops and tuppeny chews.

Beatlemania invaded my world in 1963, and I first announced my own status as a Beatlemaniac at the Lycee in that landmark year. It was the very year, I think, that I took an apparently intense dislike to an American kid called Raymond, who later became my friend. I used to attack him for no reason at all other than to assert my superiority over him. One day, he finally flipped and gave me a rabbit punch in the stomach, but he wasn't punished, perhaps because the teacher had a strong idea I'd started the trouble in the first place.

By what was probably the end of '63, I can recall that a single new group had started threatening the Beatles' position as my favourite in the world. They were the Rolling Stones; although my initial reaction to what I may have seen as a rough and sullen performance of Buddy Holly's Not Fade Away on TV, was one of disappointment, and perhaps confusion. But before long, it had become evident I'd fallen hard for the band with the outlaw image, which contrasted so violently with that of the four lovable moptops. For during a musical discussion I can remember having in about 1965 with some of the new breed of English roses, who, if they had favoured such totemic Swinging Sixties fashions as mini-skirts or kinky boots, Marianne Faithfull tresses or spartan Twiggy crops, would have been typical, I proudly announced my allegiance of the girls was a Fab Four loyalist and had the requisite seraphic smile as I recall, while another preferred the Animals, and may have acted cooler than the rest of us, as if those Geordie Bluesmen were somehow superior to mere Pop acts like the Beatles.

During this golden era, I divided my time between the Lycee and my West London stomping ground, and from a very young age, took Judo classes in South Kensington. It was there, where I earned the nickname “Alley Cat” from one of the kids, that one of my teachers, a former British international who'd fought in the first ever World Judo championships in Japan, was quoted as saying that he always knew it was Saturday once he'd heard my voice.

Later, I took classes at a club in the somewhat rougher district of Hammersmith, but if I thought I was going to raise Cain there I had another thing coming, given that its owner was a one-time captain of the British international team who'd served as an air gunner with 83 squadron during World War II. He later held Judo classes in Stalag 383.

I went on to study Karate there in the early 1970s, and was still doing so as late as 1973, when I got it into my head that I no longer wished to have anything to do with anything martial, precious blooming aesthete that I was.

For all that I was rarely happier than on those Wednesday evenings when I attended my beloved Wolf Cub pack, and I was less of a menace there than pretty well anywhere else I can think of.

Memories such as the solemnity of my enrolment, and being helped up a tree by an older cub to secure my Athletics badge, stayed with me for many years afterwards, as did the times I won my first star, and my swimming badge, with its peculiar frog symbol, as well as the pomp and the seriousness of a mass meeting I attended, with its different coloured scarves, sweaters and hair, and the tears I shed afterwards, despite the kindness of the older cockney kids who were so eager to help me find my way back home to Chiswick High Road.

There was a point in the mid 1960s when I was dubbed Le General by a long-suffering form teacher at the Lycee in consequence of what she presumably perceived as my dominance in the playground with regard to a tight circle of friends, and my tongue-in-cheek superciliousness in the classroom. This typically saw me at the back of the class leaning against the wall pretending to smoke a fat cigar like a Chicago tough guy. One thing is certain is that I was not above organising elaborate playground deceptions.

One of these involved me pretending to banish one of my best friends, Bobby, from whatever activity we had going on at the time. He played along by putting on a superb display of water works, which had the desired effect of arousing the tender mercies of some of the girls. They duly rounded on me for my hard-heartedness, but I refused to budge. Of course it was all a big joke, and Bobby and I had never been closer.

I can remember going around to his house to lounge on his bed, watching The Baron or Adam Adamant, before staying the night at the central London home he shared with his recently widowed American father, who was a gentle, melancholy man as I recall him. In '67, he spent a week with me in rural Wales as part of a course known as the Resourceful Boys. This was a combination of a simple sailing school and what could be termed outward bound activities which involved us living in tents and cooking our own food under the supervision of older males known as “mates”. I spent one week there with Bobby, and another with my much cherished cousin.

If I was Le General at the Lycee, back home I saw myself as the leader of the kids whose houses backed onto the dirty alley that ran parallel to our side of the Esmond Road in those days but has almost certainly vanished by now.

One fateful day, I crossed the road to announce a feud with the kids of the clean alley, so-called because unlike ours it was concreted over rather than being just a dirt track. It was to cost me dear. Soon after the feud had thawed I went over to pal around with some of the clean alley kids who I now saw as my allies, but there must have still been some bad blood because before long a scrap was under way and I was getting the worst of it. Finally I agreed to leave, and as I shamefully cycled off, one of the clean alley kids kicked my bike, which squeaked all the way home in unison with great heaving sobs.

If my good mate, local tough Paulie, had been with me on that afternoon in the clean alley, it's likely I would never have had to suffer as I did. Paulie lived virtually opposite us in Bedford Park, but he was from another dimension altogether. He was a skinny cockney kid with muscles like pure steel who seems to me today to have been born to wage war on the bomb sites of post-war London. For some reason, he became devoted to me; “Carly!”, he'd always cry when he wanted my attention, and he'd always be welcome at our house even though this brought my family some opprobrium within the neighbourhood. One of my mother's closest friends warned her of my association with Paulie as if genuinely concerned I might end up going to the bad, but he was a good kid at heart, and one of my dearest memories from my long gone days as a London alley cat.

Wicked Cahoots

When he made

his first personal appearance

in the dirty alley

on someone else’s rusty bike,

screaming along

in a cloud of dust

it rendered us all

speechless and motionless.

But I was amazed

that despite his grey-faced surliness,

he was very affable with us...

the bully with a naive

and sentimental heart.

He was so happy

to hear that I liked his dad

or that my mum liked him

and he was welcome

to come to tea

with us at five twenty five...

Our “adventures” were spectacular:

chasing after other bikesters,

screaming at the top

of our lungs

into blocks of flats

and then running

as our echoed waves of terror

blended with incoherent threats...

“I’ll call the Police, I’ll...”

Wicked cahoots.

All at Sea in the Glam Rock Epoch

In September 1968, I became, at just 12 years old, the youngest serving Cadet RNR at the Nautical College, Welbourne, a naval school for boys aged about 13 to 18 situated near a pretty little Thameside village in the county of Berkshire; and possibly also in the entire Royal Naval Reserve.

Founded in 1919, she was still known by her original title when I joined, but by early 1969 this had been abbreviated to Welbourne College. However, the boys retained their officer status and spent much of their time in naval officers' uniform, which would be formal solely for ceremonial occasions such as Sunday parade. While there was something known as Rec Rig, consisting of blazer and flannels or something akin, which was worn during the week when venturing beyond the bounds of the college.

In 1996, she became fully co-educational, and is now a successful public school with a strong naval tradition.

During my time there, Welbourne could be said to have provided the character-forming rigours of both a military institution and a traditional English boarding school. And I think it's fair to say the Welbourne I knew had strong links to the Church of England, and so was marked by regular if not daily classes in what was known as Divinity, morning parade ground prayers, evening prayers, and compulsory chapel on Sunday morning.

I'm indebted to her for the values it instilled in me if only unconsciously. They were after all the same values that once made Britain strong and great; and yet, by the time I joined, they were under siege as never before by the so-called Counterculture. While failing to fully understand the implications of the cultural revolution of the late 1960s, I passionately celebrated its consequences, and took to my heart many of its icons both artistic and political, and that's especially true of the Marxist revolutionary leader, Che Guevara.

In 1970, we moved from Bedford Park to West Molesey, a largely working class district close to the Surrey-London border, while our own enclave contained a mixture of residences, with some being decidedly desirable.

I left Welbourne in the summer of 1972, soon after which I was launched by my father on what could be called an intensive programme of self-improvement. And '72 could be said to be the year in which the seventies really began, as the excitement surrounding the Alternative Society started to fade into recent history. For my part though, for its first two years or so, I'd despised its commercial chart Pop, being of the Hard and Progressive school, and so a devotee of Led Zeppelin, then Deep Purple...and at some point also, Yes and Emerson Lake and Palmer, both Prog Rock passions of mine. But for better or worse, the Glam Rock epoch was going to be my era, inasmuch as I'd really been too young to be a true child of the '60s.

In late '72, I saw former Bubblegum band the Sweet on a long-forgotten teenage programme called Lift off with Ayesha, and with all the passion of a former enemy, I became entranced by their frenzied fusion of Pop-flavoured Hard Rock and outrageous high camp image. While several months later in January 1973, David Bowie appeared on the popular chat show Russell Harty Plus with his eyebrows shaved off and sporting a glittering chandelier earring, and it would be hard to recount the impression such a spectacle made upon me, given I'd never seen anything quite like it.

During this Glam Rock epoch, there were popular songs by acts such as Slade and Gary Glitter that were like football chants set to a stomping beat; while even former skinheads were now sporting shoulder length hair, as was the idol of the Arsenal, Charlie George, who had something of a Pop star image, and even cut a record. Such a scary time to me, but so exciting too, I loved it, lapped it up. It was as if the spirit of Weimar Berlin with its unholy mix of violence and decadence had been resurrected in old London town.

With regard to the previously mentioned programme, through home study and with the help of local private tutors, I set about making up for the fact that I'd left school at 16 with only two GCE - General Certificate of Education - exams to my name, at ordinary level, of course, which is why they were called O-levels.

I took Karate classes in Hammersmith, and among my fellow students were hard-looking young men - some of them flaunting classic '70s feather cuts - who may have been led to the dojo by the prevailing fashion for all things Eastern, such as the films of Bruce Lee, and the Kung Fu television series.

There were swimming lessons at the Walton Swimming Pool, where I fell hard for a softly beautiful girl with a close crop hairstyle which made her look a little like a skinhead girl. I think she beckoned to me once to come and be with her but I just stood there as if frozen to the spot. My heart wasn't in the swimming though, and this soon became clear to one of the teachers who asked me why I was even bothering to turn up.

I was taught the basics of the Rock guitar solo by a shy middle-aged man whose old-fashioned short back and sides and baggy trousers belied a deep love of the rebel music of Rock and Roll. I probably learned more about music Rock from him than anyone alive or dead, with the possible exception of a Welbourne friend, whose songs I stole with their simple chord progressions, which went from C to A minor, and then to F and on to G and then back again to C and so on.

While still only 16 as I recall, I joined the Thames Division of the Royal Naval Reserve as an Ordinary Seaman, attending classes once a week on HMS Ministry on the Embankment, and not long afterwards, it became clear to me that I'd been singled out for my budding pretty boy looks. I think this came as a bit of a surprise, but I was flattered rather than offended, as if a seed of narcissism had somehow become implanted within me in late adolescence. I can only wonder what effect this had on my healthy development as a normal male human being.

It's not that I wasn't aware of being good-looking before '72, because there had been the occasional comment about my looks on the part of female friends of the family for some years, and I'd even been made aware of being handsome as a very young boy by some of the Lycee girls. However, none of this had ever really registered with me, because I'd always been a typical feisty ruffian of a boy in a lot of ways. Having said that though, I was dreamy and imaginative to an extreme degree, which points to what would today be termed a feminine side, and I'd never gone through a phase of finding girls drippy or whatever. In fact, from as far back as I can remember I'd been prone to falling hopelessly in love with them, especially if they were somehow unattainable to me.

What's more, I was a born romantic, cherishing a grossly sentimental streak all throughout my teens that placed me somewhat at odds with my peers. While still only about fifteen and a bit of a lad on one hand, I was yet susceptible to powerful tear-jerkers such as South Pacific…whose movie version I saw at the flicks with my mother, an experience I've never forgotten.

British director John Schlesinger's screen adaptation of the uber-romantic Thomas Hardy novel Far from the Madding Crowd was another film that affected me very deeply indeed…too deeply perhaps for an adolescent boy, and it may have been partly responsible for an obsession with lost love and high romantic tragedy that remains with me to this day.

I'd an almost mawkish side to my character even as an adolescent, and this must surely have exerted some kind of influence on the course of my life, but in no way was I a typical delicate sheltered milquetoast; far from it. For this reason, to realise that I was perceived by certain other men as a pretty boy genuinely took me back, and I hadn’t seen it coming, although - and I can't emphasise this enough - it was a source of fascination to me, not shame.

The cult of androgyny was a powerful force in Britain in the early '70s, having been incubated first by Mod and then Flower Child culture, as well as Rock acts such as the Stones, the Kinks, Alice Cooper, T. Rex and David Bowie. Furthermore, it was reinforced in the cinema by several movies featuring angelically beautiful men. And yet, I think it's fair to say you still took your life into your own hands if you chose to parade around like a Glam Rock star in the mean streets of London or any other major British city - to say nothing of the countryside - and therefore few did. At least, I never saw them.

One of my big heroes as a boy had been all-American actor Steve McQueen, who incarnated an uncompromising tough guy cool. And yet in '73, several of my new idols could be said to have been “prettier than most chicks”, as T. Rex kingpin Marc Bolan once described himself. I can only wonder what effect this had on my healthy development as a normal male human being.

I fantasised about fame and adulation as a Rock and Roll or movie star as never before throughout the Glam era, and built an image based on David Bowie, spiking my hair like him, and even peroxiding it at some point. Not surprisingly then, I didn't fit in in new home town as well as my brother, who was far more suited to the area than me with his strong cockney accent and laddish ways. He wasted little time in becoming part of a local youth scene centred mainly around football, traditional sport of the British working classes.

For my part, I came into my own in Spain, or rather the Mar Menor, a large coastal lake of warm saltwater off Murcia's Costa Calida in southeastern Spain, where the family had been vacationing since about 1968. I think it was towards the end of my summer '73 holiday that I finally started to be noticed in a big way by the local youth, most from either Murcia or Madrid, and so la Ribera became vital to me in terms of my becoming a social being among members of both sexes. A large ever-evolving group of us became very close and remained so for four summers running. Spain was such a sweet and friendly nation back then in the relatively innocent early seventies, and the youth of La Ribera as happy and carefree as I imagine southern Californians would have been in the pre-Beatles sixties.

What a time it was, a time of constant, frenetic change when everything seemed to be mine for the knowing and the tasting in the wake of a social revolution that had been all but bloodlessly waged on my behalf only a few years before; but there was a high price to be paid for all that gambolling.