Samhain

Whispers in the dark. The dull edge of hushed, panicked voices. An ochre corona etched away at the darkened frame of the bedroom door. The high-pitched squeal of the old hinges protested as the door slowly opened. My mother; her outline indistinct against the light: silently gestured for me to come out of bed. As I rounded the bottom of my parents' bed, I felt compelled to squeeze my father’s foot through the heavy woollen blankets; his breaths were erratic and ragged.

Confused, I sat at the edge of the sofa; my youngest sister was perched on the small stool in front of the kitchen stove…rocking back and forth, weeping quietly. Someone had gone to fetch the doctor.

Shortly before four o’clock on that still, Autumn morning, the doctor finally arrived; immediately ushered upstairs. In the edged silence of the kitchen where most of my family sat, the only sounds were of weight being shifted from one upstairs floorboard to another…each board protesting with varying degrees of vehemence.

This went on for several minutes…but then it stopped entirely and the doctor slowly came into the kitchen to stand before us; this tall gaunt woman with short grey hair, a low contralto voice and a stethoscope permanently draped round her neck like a mayoral chain of office: all eyes trained on her in expectant fear. She cleared her throat once, twice, before:

“He’s dead.”

And then ~ stillness. Silence.

Samhain, the greatest of the ancient Gaelic festivals, marked the end of the old year and the beginning of the new. The seasons of loss and regaining. After the plentiful harvest of Lúghnasa, the Celtic new year began in the cold lengthening shadows of winter.

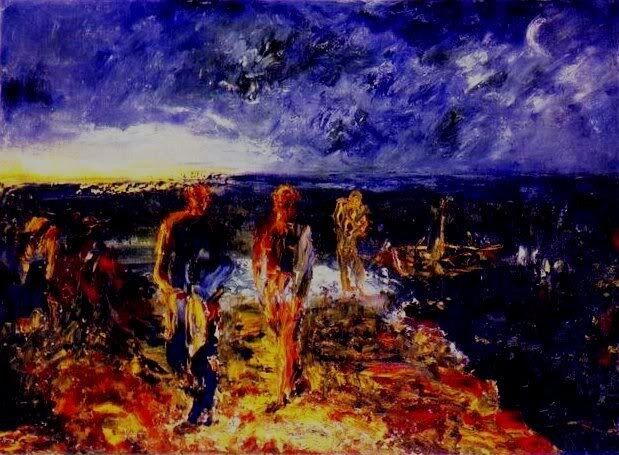

Celebrated with bright bonfires and dark rituals; Samhain was the night that the barrier between the living world and the Otherworld became porous and translucent; the night when the dead could step across with ease and return home from the night-lands of that other place. Seasonal foods of fruits, berries and nuts were laid out as a feast in their honour and they were fully expected to partake of the feasting. Their faces were seen in the flames of bonfires on every hill and their voices were heard on every keening breeze.

It was a night of quieter, darker rituals too. Of great swords, sacrificed to the river goddess; their bright, deadly blades broken, their intricately decorated hilts unfixed. And of failed kings; their nipples sliced off, their arms pierced with hazel withies: sacrificed to the goddess of war and death. Terrible rituals performed to ensure the survival and prosperity of the tribe.

Rituals now lost to memory; merely hinted at by grim, millennia-old discoveries made in bogs in the West of Ireland.

The pizzicato of droplets returning to a porcelain washbasin. A shaft of ochre light dissecting the carpet on the landing. The vigorous quarrel of a double-edged razor in cleansing argument with the water.

And later ~ the creak of the wooden stair-boards as he brought tea and bread to my mother; still in bed: before leaving in the gathering light of a chill morning.

And then ~ stillness. Silence.

It’s the little things that you remember; which matter most.

That simple morning ritual was the secret of their long and happy marriage. Every morning he would bring her tea in bed before going to work.

My father was a forester and gardener. During the week, from Monday to Friday, he was part of a team sent out by the Forestry Department to look after and maintain the many forests and woodlands of Donegal. Then at the weekends he would tend the gardens of a number of large houses in the area.

When I was young the word ‘forester’ was unknown to me; so on those rare occasions when the teacher would go round the class, asking everyone what his or her Daddy did for a living, the only word I knew to describe what my Daddy did was a word I’d read in a fairy tale. Most of my classmates gave fairly standard answers; Garda (policeman), teacher, farmer, shopkeeper etc: but when it came to my turn I would invariably answer…Woodcutter! It was the only word I knew. Though it did make me suspect that I might be Little Red Riding Hood.

At the end of long summer evenings I would wait for him at the top of the hill above our house. Shortly after six o’clock, I’d hear his voice as he chatted with his friends George and Willy on their way home. Then I would see them appear over the brow of the hill on their bicycles; laughing and joking as they cycled leisurely in the seemingly forever golden sunshine of Lúghnasa.

When they reached me, my father would swing off his large black bicycle and lift me, with one smooth movement, onto the saddle: then wheel me round the back of the other houses to the top of the steep stone steps which led down to our back garden. Juddering down the steps; safely looped in my father’s arm: was my favourite part of my little joyride every evening. Once we reached the back doorstep, he’d lift me down and put the bike in the shed for the night.

Every Friday when we got into the house he’d take his wage packet; a small brown envelop with a plastic window: out of his back pocket and hand it to me.

“Give that to your Mammy”

I would do so almost reverently; though the purpose of this eluded my fanciful imagination, the ritual did seem particularly significant…pregnant with a conveyed meaning beyond my childish grasp.

In the evenings, after dinner, he would sit in the back kitchen listening to the wireless (radio) before falling asleep in the brown threadbare armchair behind the kitchen door; his head pitched at an odd angle, black-rimmed glasses perched askew on the bridge of his nose and his mouth lying slightly open as he snored softly.

I loved sitting on his knee in that armchair. And I loved taking over that armchair when he wasn’t sitting in it. The straps beneath the cushion sagged so badly that we had to place a stool beneath them to prevent us from falling through onto the floor; but still, I loved sitting in that chair for hours, listening to abridged children’s versions of The Hound of the Baskervilles and Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde on my Walkman.

Oíche Shamhna (the Night of Samhain) became All Hallow’s Eve after the Celtic world was painted with the thin veneer of Christian piety. When I was young we still spelled it Hallowe’en, though even the apostrophe has been lost in the intervening years.

The memories of my childhood Hallowe’ens are overlaid with the smell of wax crayons. At school, in the days before the holiday, we would each make our own Hallowe’en masks. Oblongs of card were cut from the backs of cereal boxes; eye, nose and mouth holes were carefully measured and cut out to fit each individual: then we’d colour the masks with bright, garish crayons, the smell of the wax filled the classroom, with its tiny new desks and the huge old maps of Ireland, Britain and Europe lining every wall.

On Oíche Shamhna itself; the beginning of a weeklong school holiday: we would go ‘mumming’ (the traditional precursor to “trick or treating”). ‘Mummers’ were (mostly!) children dressed in costume, going from door to door, singing songs and reciting poetry in exchange for sweets, fruit and money.

A Hallowe’en party had at its centre the Báirín Breac: a traditional cake of sweetbread with raisins and sultanas. Each brack had a number of symbolic items baked into it, which prophesied what would happen to the recipient in the coming year. If your slice had the ring, you’d be married within the year, if you got the pea…marriage was not on the cards; though if you found a stick or twig in your slice, your marriage would be an unhappy one. A coin prophesied great wealth, a small piece of cloth indicated encroaching poverty.

We also played a number of traditional games. The one which sticks in my mind is ‘bobbing for apples’; several pieces of fruit (apples mostly, along with oranges, pears and even nuts) were put in a large basin of water and we took turns trying to take one out using only our mouths. It’s even more difficult than it sounds and usually ends with everyone getting very, very wet!

The year that I turned ten, my father took early retirement from his job in the forestry a few days before Samhain. To me, this meant that Daddy would be round the house a lot more…something to which I was very much looking forward. He officially retired on the Friday; just three days before Hallowe’en: but hadn’t been feeling well. As he attended the doctor’s clinic that evening, we prepared a Retirement/early Hallowe’en party in his honour at home. The added joy of surprising Daddy with a party and the fact that we would get to have another one the following Monday; which was actually Hallowe’en: made that night the best, most fun, Oíche Shamhna of my childhood.

That night we went to bed exhausted but happy.

Whispers in the dark. The dull edge of hushed, panicked voices.

When someone important and close to you dies, the very contours of your world change. The reassuring obelisk of their presence is suddenly gone and the boundaries which defined your safe, self-contained landscape become porous and translucent … and then they disappear altogether. The world becomes wider and darker; the cataclysmic shift permanently tilts the earth’s axis and what once seemed solid and assured reveals itself to be fleeting and ephemeral.

The barriers between this world and the Otherworld do not lower at Samhain ~ they were never there to begin with. There is no Otherworld from which to retrieve that which was lost; no night-lands to return from. The dead stay dead.

There are no faces in the flames; no voices on the keening breeze. There are only the delightedly terrified screams of children, dressed in garish costumes and masks, as they run from house to house singing songs and demanding candy with menaces. They enact a game based on a tradition derived from ancient ritual lost to myth and memory long ago.

“He’s dead!”

With those two simple words, the bottom fell out of my world.

In the dull light of an Autumn morning they placed my father in the ground; twenty-nine Hallowe’ens ago.

I wasn’t allowed to go. Children may be an integral part of Weddings and Wakes, but they’re rarely tolerated at Funerals…even today.

I would paint for you a picture of the cold overcast morning they buried my father…but I wasn’t there.

I would give you a detailed description of the Funeral Rite, of the Benediction and Eulogy…but I don’t know.

All I know…is the true, ancient and original significance of Samhain.

And I know the stillness. And the silence.

A note on pronunciation:

Samhain: Sow-inn

Lúghnasa: Loo nas-ah

Oíche Shamhna: Ee-heh How-nah

Báirín breac: Baar-een brack

Comments

Hey sweetheart, you know I love this so so much. I adore the way in which your memories are written in contrast to the actual message. This is filled with so much detailed emotion as the words melt from the page, it pulls at my heart. It's so honest and direct but with such heartfelt sincerity. You see the world around us in such a unique way and this shows so well when you write. He was obviously a very amazing man that you treasure in such wonderful and sorrowful memories.

I love you so so much and this is just amazing...a bit like the writer himself

Your Lorna xxxx

Thank you so much...my darling.

There are so many...too many...things I should thank you for; and your constant encouragement and support gives me the will to go on.

I love you so much...and endeavour to, hope to, do the same for you.

Your Jason XxXxXxXxXxXx

Wow this a great and wonderful poem a masterpiece well done

Thank you so much, Greg.

This one means a lot to me...as does your comment.

J ;)

My Dear Friend Jason,

My dear friend Jason has written

A tale called "Samhain"

And before I make a comment

I must absorb it in my brain

.

I ask for his indulgence

A day or two injest

His words of utter brilliance

Before I take my test

.

Your forever friend,

Larry xxx

My Dear Friend Jason,

I have just finished reading this masterpiece. It brought tears to my eyes to think that you lost your wonderful Father, whom you loved so dearly, at such a young age. Instead of leaving you a long comment here, I am now in the process of writing a lengthy poem devoted to you and your Beloved Father. I have named it "The Woodcutters' Son". However, I will now give you a Haiku as part of my response.

A Fathers dear love

So treasured by his young son

Too early had part

.

Love,

Larry xxx

Larry, my dear friend...

I really don't know how to respond, other than to say, Thank You.

As you can possibly imagine, this piece has been turning itself over in my mind for a long time now; in fact, I wrote a much shorter, embryonic version of it as an essay for school when I was twelve or thirteen.

I'm so glad that you, especially, have read and responded to this piece. Having some small inkling as to your own parent/child problems (which are behind you now, thankfully), I was rather hoping that you would read this. Honestly, I had no definable concrete reason for hoping this...just a feeling that you would get something from it.

Please give Linda all my love.

I remain...your friend & fan,

Jason

Dearest Jason.....I am struggling to find words that say how your poem has affected me! It's such a beautiful tribute to filial love that encompassed paternal love and familial love - interwoven with a nostalgic journey through a magical childhood . It is just lovely! thank you so much for sharing this really personal memory.

Lodigiana xxx

Thank you so much for your kind words.

We both know that writing is not really a job...it isn't even a calling, or vocation. It's a need! Put simply, we need to write!! Not only do we need to expel the words, images and ideas that are ever-turning in our minds, but we then need to put more refined shape on those words, images and ideas to create a journey for others; a journey, at the end of which some may even hope to discover themselves (the poor fools!?!).

If we read to know we are not alone ... then surely we write to say to the world: This is me...good, bad and indifferent.

I needed to write this. And I'm glad that you enjoyed the journey.

J ;)