It took Five Cities, Two Weeks and One Tower to change me...

When the sound of One Republic filled my ears in the early hours of July 2016, my eyes opened like a cheetah chasing prey. During the last three weeks I’d paced to and from the little stationary shop, where I worked, along the littered streets of Putney, while my family drove through Bordeaux. Today was the day I got to meet them in Valencia. Thirty minutes later I was dressed and ready, sitting on the edge of my bed staring at my suitcase, my knees bouncing with excitement.

This was my first flight that I’d ever taken by myself. The responsibility felt heavy on my shoulders. I checked on my passport and boarding pass continually in the back of the taxi. The idea of everything I was set to see soothed me- the Valencia Aquarium, The Canadian War Memorial and of course the Eiffel Tower. I sat on the plane, and silently congratulated myself on making it to the right place at the right time. I took my notebook out of my handbag and looked at its cover- the tower’s point defined and elegant, like a ballerina’s pirouette. I sat next to a rather handsome stranger who spoke in a strong Spanish accident, which the air stewardess found difficult to understand. Throughout the flight his fingers drummed on my arm rest, a rhythm I didn’t recognize, but I was too polite to ask him to stop.

Three hours later I followed the sea of passengers floating towards the Valencia arrival lounge, each followed by the consistent hum of their suitcases. I was greeted by my family all displaying excited smiles and premature sun- kissed shoulders.

We dropped our bags off in the hotel and left soon after to visit Torres de Serranos, one of the twelve gates creating an Ancient City wall, built in the late fourteenth century. I’m no historian, but I’ve seen countless castles, with the same turrets; just different flags. For weeks I’d looked forward to sitting in the sunshine with an iced coffee but Mum insisted we “immersed ourselves in the city’s culture” So we hiked to the top of the ruin that was once a prison to store the nobles.

It was only after we had seen the view from the top, that we realised Valencia was a town you had to be immersed in to appreciate its beauty. The buildings themselves were flat and lived in, with rooftop gardens that were just another room to hang your washing. It was the people I found myself looking at, going about their daily business; eating on unstable metal furniture and talking to grocery stool holders.

While walking through the town we stumbled on a shop with an orange sign hanging on a rusted chain that read Bike Rental. I was reluctant to go in at first, noticing it was an English sign, which meant we were subconsciously encouraging the ignorant English tourist stereotype. Living in London, I have experienced bumping into more than my fair share of tourists taking selfies in inappropriate places, like in the middle of Waterloo Bridge. When I saw the retro pastel blue Viking Belgravia bike standing in the window however, my eyes lit up like sparklers, and I had to make an allowance. We followed the gravel path all the way to Turía Gardens. The breeze was fresh, ridding the sweat from my back, as we rode past underwhelming fountains; green grass and trees too healthy to have relied on the sparse Spanish rain alone to survive.

I awoke the next morning with an aching backside, excited to see L’Oceanográphic- an aquarium so large its futuristic buildings alone had become a Valencia tourist attraction. Despite being followed by a herd of yapping school children, the sea horses sprouting out of their backs and the walruses kissing the glass lingered on the back of eyelids. I saw penguins jump and swim like they did in the movies and flamingos a tinted rosé colour, in a cluster that looked like gossiping housewives, picking their kids up from daycare.

That evening, with stomachs full of calamari and pancetta, we drove to Alicante to spend a week in the apartment I’d spent the summers of my childhood and pre-adolescence. The familiarity came as a comfort after exploring foreign streets, not knowing what was around each cobbled corner, and the lack of itinerary felt like a blessing. We visited Casa La Padrerer (The House of Stone, that appeared on Grand Designs), which stands on a mountain top, hidden, with a deep, heavily chlorinated swimming pool. It looks out onto a turquoise lake so picturesque it may as well have been created by Walt Disney himself. The owners of the house had set up rafting, canoeing and quad biking tours. So although peaceful, the roar of engines rose and fell around you and those who had just returned from trips arrived in clouds of dusts and smiles of accomplishment.

A week later we had detoxed and were back on the road. I hadn’t heard of Gerona until Mum suggested it last minute to break up the ten hour journey to Verrieres; our last stop before Paris. We threw our bags down in the budget hotel, where the corridors smelt of dogs and the beds were soft and the pillows thin. We walked into town, which was full of streets narrower than Valencia, each one shadier than the next. Each apartment window displayed geraniums that intertwined around filigree balconies. They were probably purchased from one of the many florists that were sprinkled like confetti throughout the town. We made it to Plaza de la Indepencia, which separates the old town and the new. It was difficult finding a cafe amongst the many seafood restaurants but we got a table facing the statue in the centre of the square. It commemorates Gerona’s fight for independence, bordered by clean unmarked marble and flower wreaths that lay at the foot; placed there after the recent anniversary. It wasn’t much taller than the parasol I sat beneath, and a hell of a lot shorter than the Eiffel Tower. But there was still an aura of demanded respect surrounding it; something in the lack of bird shit, when the paths I walked upon were littered with it as if even the birds appreciated the suffering. We ate dessert in one of the many creperies, and after remarking on the sweetness of the strawberries the waiter gave me a handful to take away with me.

The next afternoon we drove across the tallest bridge in the world, the Milau Viaduct, a monstrous steel structure held together with metal poles which from afar looked like silver harp strings. On either side there was greenery so perfect- like Middle Earth had escaped from my book. Each road felt infinitely long meandering through Aveyron, a department of Southern France, specifically in the Occitanie Region. I was unsure if it was the altitude or the never-ending car journey that was making my head spin. I longed for an icy swimming pool and a drink other than the warm squash that sat in the glove compartment.

We pulled into a slanted car park and waited in the garden for someone to check us in. Flies danced noisily around the wild flowers surrounding us as if they were jealous of us humans playing rummy on this ivory table. We sat beneath what little shade we could purchase from the trees and waited for the owner who was now over an hour late. When she arrived, Yvette wore a beige linen skirt and a silk neck scarf of fiery colours. Speaking with a thick French accent, she apologized for letting time get away from her. My brother and I were shown our room first, a small space with a double bed and a single on the level above. The ceilings were imposingly low and the furnishings had a mustard tone that matched Yvette’s neck scarf. There were no doors to mark the shower, just two pieces of wood about five feet tall. In the light of day the rooms looked old fashioned but quaint, and brimming with culture. We unloaded our bags and made our way to the pool in the short time before dinner was served, and only then did I notice the altitude had brought with it a breeze brisk enough to make the pool uninviting. I lay on the sun bed watching a German family enjoy their last day. “Vater?” the little girl asked with tight Dutch braids, proceeding with a question I couldn’t comprehend. It was here I realized no matter the nationality all little girls are curious.

The food served was extravagant, with Roquefort cheese that tasted both foreign and comforting. My brother held my arm on the walk back to our room, an ally in the battle between my wedges and the cobbled path. In the dark of night our room had transformed into an abandoned mustard ruin. When the lamp was turned on, it highlighted the ants that inhabited the stone walls of the stair case. My brother came across a spider upstairs giving him a fright; big enough to make him sleep downstairs with me.

‘Please don’t tell Dad I couldn’t sleep in the Harry Potter closet room Ellie, can we pretend I did’ he whispered.

I’m sure while I was kept awake with idealistic visions of the Eiffel tower dramatically lit up, like fire, Ben had nightmares of enduring Dad’s endless jokes and teasing all the way there.

The views seemed to compensate for our sleepless night. The houses around us grew crops as part of their livelihood, so the colours bled across the soil, like a growing kaleidoscope. Breakfast was underwhelming, consisting of a croissant, French set yoghurt and orange juice; with coffee so bitter your face screwed up like yesterday’s newspaper. But I didn’t mind because today was the day I had been dreaming about for a decade. Today was the day I got to see the Eiffel Tower.

A broadcasting tower made of wrought iron lace; iconic enough to illustrate an entire country, becoming the most visited paid monument in the world stood 625.9 kilometres away. I usually hated the idea of becoming the tourist- feeling self-conscious, traipsing around a foreign city with a camera around my neck and a map in my back pocket, but this time it didn’t matter. I felt as though this Tower had been waiting for me, and only me, to visit. I had been obsessed with it from the age of seven, after I saw it in the background of a Bratz video I plaid. From that moment I’d plastered it over my stationery, bed linen and canvases. The rest of my family had seen the tower before and had felt underwhelmed. Desperately they tried to distinguish my excitement so that I wouldn’t be disappointed...

My knee started to bounce from the moment I saw the first road sign for Paris.

“It’s just a building, Ellie. I mean, it’s pretty, but you should be way more excited about the food!” said my brother, who felt the movement in the seat we shared.

I was the first to see it in the distance, three times the size of the buildings surrounding it, an unmistakable shape different from anything I had ever seen before. I felt star-struck, as if I’d finally met the celebrity from the ripped magazine pages on my wall.

That evening we visited the Montparnasse Tower, a 210 metre skyscraper that gave you the best view of Paris, because it was the only building that gave you the full skyline, including the Eiffel Tower. We took the Metro to Montparnasse- Bienvenue. The map looked confusing at first, lines criss-crossing through each other, like the entangled bead frames children play with in dentist waiting rooms. But after noticing it’s similarities with the London tube map, it became easier to distinguish the different lines and stations. The tunnels themselves smelt of sulphur and the rough fibres of the seats scratched my skin. The carriage rocked violently around the corners, I clung on to a cold pole for support, but my sweaty palms lessened my grip.

I had underestimated how tall the building was. With seven-thousand two-hundred smoke windows piled on top of each other, I couldn’t see where they ended and where the sky began. The city lights reflected off them making me feel vulnerable in this huge foreign city. Ten of us squeezed into the elevator and thirty nice seconds later we were catapulted one hundred and ninety six meters to the fifty sixth floor. This consisted of an overpriced cafe and interactive screens where you learnt about the different landmarks. It was here I found out that the Eiffel Tower was originally temporary. In 1909 the government intended to scrap it, but instead saw it’s potential as a radio telegraph station. This ultimately, helped the French to distinguish enemy radio communications during World War One. The Eiffel Tower was the only building I was interested in, so I ran ahead of my family up the stairs to the terrace, also known as the fifty ninth floor. I froze- partly because of the biting wind coming through the grated ceiling, but mostly because I was in awe. This was the first time I had seen the Eiffel Tower without distraction; without missing a quarter because of where I was standing or for a split second while driving. It glittered at me and only me, as if covered with sequins, my sequins, and it was everything I had dreamed about and more. The vision of it has haunted me ever since- the way it looked alive with four legs and threatened to trample on the measly and vulnerable buildings around it. The lattice so delicate it should be tied with a ribbon at the top in order to keep it all together. The overwhelming twinkle of gold made me feel as though I was witnessing a secret I had no choice but to cherish.

The next morning in the daylight we walked down the River Seine past the Notre Dame. It was littered with French security guards, after a Priest’s throat was slit by an Isis terrorist. But the city still looked quaint, fragile and cultured with its narrow river and not one bridge looking the same as the next. When we reached the Eiffel Tower, it looked darker, as if last night we had visited the celebration and today was the day things returned to normal. But it was still just as delicate as it had looked the night before. Only we saw the greenery surrounding it, flustered with bottle tops and packets of left over Marlborough lights, after the Euro finals that had finished three weeks before. We sat on the hard ground and thin patchy grass, looking up at it’s summit. Young men snaked through the families surrounding us, selling bottles of wine, beer and water. I fell asleep on my father’s lap amongst the litter and the sunshine creeping out through the clouds; the two weeks of travelling finally catching up on me. The road trip was now coming to an end, one stop left before the ferry from Calais.

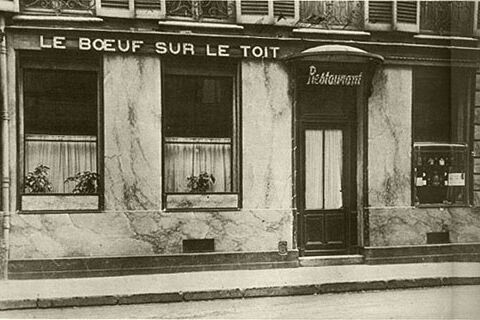

We visited a Parisian cafe in a last attempt to stay longer in the city I’d dreamed about since I was a little girl- we set off for Vimi. The idea of a war memorial didn’t interest me much, but it pushed down the dread of returning to normalcy back into my gut. Soon we would be on the ferry driving in on the right lane and driving out in the left- signifying the end of the trip.

We drove past countless memorials, cemeteries and graveyards- so many we felt guilty not knowing they existed. Vimy Ridge was situated on a minefield, a maze full of tunnels, trenches and timber. Most mines had already exploded during the war but there were signs telling visitors to stay on the path in case they were still active. The Canadian Memorial Statue is the largest of Canada’s war monuments- an ivory structure, not as tall as the Eiffel Tower but placed on the highest point so it’s background consisted of nothing less than the overcast sky. As we walked closer we absorbed everything it represented, stroking the 11,161 names engraved on its base, each an obituary for a French soldier without a grave. It wasn’t until I felt them on my fingers that I imagined their family’s grief. There must have been fifty other people around me and yet everything was silent. The statue was oppressive forcing you to reflect on yourself and everything you take for granted, out the corner of my eye I notice a single tear trickle down my mum’s cheek.

As we walked away from the memorial I hole her hand, consoling her, possibly for the lives lost, the families grieving for a body they haven’t seen. Maybe it wasn’t anything deeper than the fact we both knew in two days time we’d be back at work- back to normal. In two weeks I’d slept in five different beds, in five different cities across two different countries. I’d seen buildings that made me stand still; architecture that left me in awe and statues that made me weep. I’d experienced so many new things; I couldn’t wait to write about them in my journal describing every step, every mile, desperate not to forget a single second.